By Nitin Madhav, Washington, DC

Nitin Madhav was born and raised in Pittsburgh, graduating from Penn Hills Senior High School and the University of Pittsburgh. After his bachelor’s and two master’s degrees, he began working in public health in several countries around the world. He has traveled extensively and is an avid photographer. His work is on nitin.photography and on Instagram at @nitinmadhav.

I have never packed fourteen pairs of long underwear for a trip to India! When my friend, Behzad Larry, invited me to join him on an expedition to see snow leopards in Ladakh in November — he warned me it would be cold — I jumped at the opportunity since this was not the usual thing a guy from Pittsburgh does. I have been to India many, many times to visit family or for religious festivals, but never had to pack for the cold. This was a first — a snow leopard safari in the high mountains of the Himalayas.

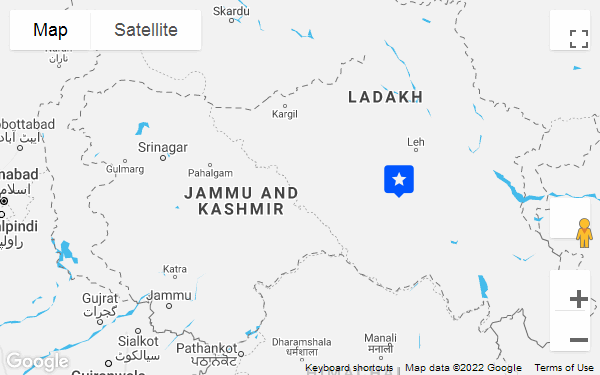

Behzad worked with his Ladakhi partners, Abdul Rashid and Dorjay Stanzin, to set up a camp for snow leopard safaris near Hemis National Park (32 miles from Leh at 16,000 ft elevation), which has only about 70-80 of these cats, out of a worldwide population of about 3500.

Behzad, who is from Indore, India and an accomplished wildlife photographer-turned-conservationist, saw a void in the tourism experience that Ladakh offered. While most people came to Ladakh to trek, there is an incredible story for these visitors to share with people interested in wildlife, especially the critically endangered snow leopards.

Conservation in India has seen a positive change in the last few decades. While there is still human/animal conflict where man is encroaching on wildlife habitat, there is a renewed urgency in maintaining the biodiversity of India. There are several national parks where one can see tigers, but few with the world’s most elusive big cat — snow leopards. Ladakh happens to be the place with the highest concentration of snow leopards in India.

The altitude is important to factor into travel plans in Ladakh. I flew from Delhi to Leh, the capital, and spent two days acclimatizing to the high altitude. I am pretty fit, but still found simple tasks like putting on my shoes left me gasping for breath. Behzad told me that this was normal, and I would acclimatize in a few days, which I did.

Since I have been on many safaris across Africa, the Ladakhi experience is not significantly different… just miserably colder. Behzad works with highly skilled spotters who can identify snow leopards on high mountain ridges from great distances, sometimes up to seven kilometers away. They depart early in the morning, radioing back to camp when a cat has been spotted. Then, we bundle up, grab our cameras, and hop into the jeep.

Snow leopards are most active at dawn and twilight, so it is key to make the most of this time. The spotters look for blue sheep, known as bharal in the local language. A hungry snow leopard will often target blue sheep in its hunt; so, if these local experts spot these sheep, it is most likely that a cat is somewhere around.

Snow leopards camouflage themselves in the rocky terrain. They roll around in the dirt before stalking bharal, covering their coats in soil. Their spots make them blend in with rock formations, making them difficult to spot. Thus, it is important to work with trained spotters who know what to look for. Sometimes, the spotters will see a cat and will try to track it; however, the cat will disappear over a mountain ridge. They carefully scan the mountains paying attention to the bharal and the condition they are in. If they are agitated or seem on edge, a snow leopard could be nearby. Sometimes the wait can take all day in the cold, which is why I made sure to pack all those long johns!

While there are others that offer snow leopard tours, it is vital to ensure that these are done ethically, without baiting the cats. When snow leopards are baited, it creates the expectation that domestic livestock are easy prey for the cat — which leads to ongoing human/animal conflict as herders can lose their entire herd to a snow leopard, and they, in turn, would prefer to kill the snow leopard to avoid future losses.

The first time I saw a snow leopard, I mistook a group of bharal for bushes, and I asked Behzad to stop for a second, when one of our trackers hollered “Snow leopard!” and indeed, it was. It was a scruffy beast, not at all like the supermodel snow leopards I had seen in photos. This was a beast who had worked hard to find every meal — and he slowly approached the bharal which fled in fear — but not before Behzad got a few shots of the snow leopard close to the bharal.

The next day, we got a call telling us that a snow leopard had gotten trapped overnight in a shepherd’s corral in a village about an hour away, and were invited us to take part in its rescue. The snow leopard snuck into a corral at night. The shepherd heard the commotion of the cat attacking the sheep, and let the other sheep out and locked the gate with the snow leopard captive inside.

The Indian Wildlife Service rangers came by, tranquilized the snow leopard and after it was sedated, brought it out of the corral and took some biometric data before releasing it into the wild.

While it was sedated, I got to pet it and be a part of the biometric measuring. It was a beautiful male cat about five years old. I have been told many times that that is an unusual occurrence — I am the only one who has had a chance to do that, of the several hundred people who have gone on Behzad’s expeditions. It was an experience I will never forget — which made the trip so much more worthwhile.

Behzad kept saying he didn’t know if he could top that experience, and to be honest, nothing quite as interesting happened the rest of the trip. But this was the thrill of a lifetime.

If you are interested in a snow leopard expedition in either Ladakh or Kyrgyzstan, Behzad is offering a discount to readers of the Pittsburgh Patrika — mention that when you contact him on his website: https://voygr.com/ ∎