By Kollengode S Venkataraman, Murrysville, PA

e-mail:ThePatrika@aol.com

Acknowledgments: M. Meenakshisundaram of Tiruchy, India for going over the drafts and offering valuable suggestions.

This article was written for the souvenir for Guha Ghosanam, a festival conducted in August, 2023 dedicated to Muruga-p-perumaan, at the Sri Siva Vishnu Temple, in Lahham, MD, a suburb of Washington DC.

In all faiths all over the world, admirers and devotees of great savants often add hagiographic embellishments to the lives of these sages, with some of these embellishments so fantastic that they confound rational minds. The admirers of Poet Arunagiri are no exception. His followers and devotees call him Arunagirinaathar (அருணகிரிநாதர், अरुनगिरिनादर), “nathar” a suffix added to his name out of their love and respect. This great Bhakti poet is known for his extraordinary poetical skills employing complex and varying rhythm patterns in his poems, his proficiency in Tamil and Sanskrit languages, and virtuosity in weaving into his poems the tenets of the Vedas, and stories from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and Siva, Vishnu, and Skanda Puranas. When you come to know of these, you too will admire him, and understand why his devotees call him Arunagirinaathar. Another unique feature in his poems is his mastery in trying to reconcile the conflicts between the Shaivites and Vaishnavites of his time.

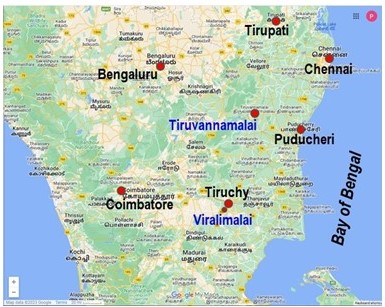

Arunagirinaathar’s Time: His prolific religious-spiritual-poetical work was in the 15th century. He was born in 1370 Current Era and died in 1450 at the age of 80. He was born in the Sengunta Kaikolar community in Tiruvannamalai, the temple town for Arunachaleshawara in Tamil Nadu. In his poems, Arunagirinaathar refers to Prabhuda Devaraayan, the Vijayanagara king who ruled over the Tiravannamalai region in the 15th century, which confirms Arunagirinaathar’s time.

Arunagarinaathar’s life and lifestyle: In one of his poems starting with மனையவள் நகைக்க… … he describes his adult life, from which we can infer that he led a married life. From the structure and contents of his poems, there are strong reasons to believe that he lived close to temple dancers in the region. Living close to temple dancers — called Devadasis, a term not always used as a compliment — he saw in close quarters the lifestyles of the dancers living under the patronage of landlords and local kings. These dancers had to make many compromises in their lifestyles to live under such patronage.

In his poems the poet vividly describes the young dancers’ charm and beauty, the jewelry and clothes they wear, and the cosmetics and perfumes they use to enhance their beauty.

In over 1600 of his poems, Arunagirinaathar candidly acknowledges his proclivity for excessive indulgence in sensual pleasures. Recognizing this, he pleads for Muruga-p-peruman’s (literally, Lord Muruga’s) grace to wean himself away from this weakness.

In all societies throughout history, in people given to excessive indulgences of all types, we see radical transformations taking place quite abruptly. As if by a miracle, people voluntarily and without any struggle walk away from their lifestyle given to excesses. We hear about people among us making these kinds of abrupt U-turns in their lives — some of us even know them personally. When we ask them how they changed so suddenly, they struggle to explain the changes using logic. They attribute the abrupt changes for the better in their lives to Divine Intervention, or God’s Grace (இறைவன் அருள்).

Such a miraculous transformation happens to Arunagiri also, who was given to a profligate lifestyle. Recognizing this, he feels so despondent about his situation, as the popular story of his life goes, that he wanted to kill himself by jumping off a smaller Gopuram in the Arunachaleshwara Temple complex in Tiruvannamalai. As he was about to jump off the tower, he was miraculously stopped by Muruga-p-perumaan (Lord Muruga) Himself, telling him, “Your life is not to be wasted, and your mission is to save the lives of fallen people.” When Arunagiri pleaded how he can do it given his background, Muruga-p-perumaan (Lord Muruga) gives him the first phrases, முத்தைத்தரு பத்தித் திருநகை (Muththai-tharu-paththi-thirunagai) and disappears.

With the grace granted by Muruga-p-perumaan, Arunagirinaathar spontaneously composes his first song right there. You can listen to his first verse here:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fp7VAfmxJog,

and listen to Sambandam Gurukkal rendering the song in pulsating and lilting rhythm.

This was a great transforming moment in Arunagirinaathar’s life. He effortlessly abandoned his reckless lifestyle, becoming a mendicant and an ardent devotee of Muruga-p-perumaan. He later traveled all over South India and Sri Lanka, visiting over 200 Siva and Murugan temples, and composed songs addressing their presiding deities. Over 1600 poems are available in an anthology called திருப்புகழ் (Tiru-p-pugazh), meaning Divine Praise, most of them addressed to Muruga-p-peruman.

Arunagirinaathar’s poems in Tirup-pugazh are known for their lilting and pulsating complex rhythm patterns, known in Indian prosody as Chandas (छन्दस् in Devanagari, and சந்தம் in Tamil), meaning poetical meter. His poems are usually four- or eight-line verses consisting of 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, or even 20 phrases in each line conforming to complex rhythm patterns. The poet keeps the same complex rhythm pattern in all the four or eight lines in each poem. This alone requires great linguistic skills purely in terms of prosody.

For example, his most popular poem muththai-tharu-paththi-thirunagai (முத்தைத்தரு பத்தித் திருநகை அத்திக்கிறை சத்திச் சரவண… …) follows the following rhythm pattern.:

tatta-tana tatta-tana-tana tatta-tana tatta-tana-tana

tatta-tana tatta-tana-tana — tana-taana

தத்த-தன தத்த-தனதன தத்த-தன தத்த-தனதன

தத்த-தன தத்த தனதன –– தனதான

Many Tamils know the name Tiru-p-pugazh, or at least would have heard the name. Not many would have read the verses or grasped their meanings. The verses have complex tongue-twisting phrases mixed with Tamil and Sanskrit words, written following Tamil and Sanskrit sandhi rules. This is difficult to grasp, especially for today’s Tamils with a limited knowledge of the Tamil language and its vocabulary because of the neglect of the Tamil in the school curriculum.

What is remarkable about Arunagirinaathar is that his skills in using complex rhythm patterns are only the base frame of skeleton in his poems. Around this frame, the poet builds complex stories giving us sensuous poems dripping in Bhakti (devotion). To fully understand and appreciate Arunanagirinaathar’s poems, one needs a good grasp of Tamil and Sanskrit vocabulary and grammar to get their basic meanings; and also to know of Sanatana Dharma’s tenets in the Vedas, Puranas, Ashtanga Yoga… … as we discussed earlier.

So, without the help of commentaries from scholars, it will be very difficult to understand and admire the prosodic skills of Arunagirinaathar and his grasp of all facets of the Sanatana Dharma. Here is a two-line example, first in the original form with the words fitted to flow with the rhythm pattern, and then with the words split to get some idea of what the poet conveys:

Rhythm pattern:

தாத்தனத் தானதன தாத்தனத் தானதன

தாத்தனத் தானதன …… தனதான

Original lyrics:

வாட்படச் சேனைபட வோட்டியொட் டாரையிறு மாப்புடைத் தாளரசர் …… பெருவாழ்வும்

மாத்திரைப் போதிலிடு காட்டினிற் போமெனஇல் வாழ்க்கைவிட் டேறுமடி …… யவர்போலக்

With words split for getting the meaning:

வாட்படச் சேனைபட ஓட்டி ஒட்டாரை

இறுமாப்புடைத்து ஆள் அரசர்… … பெருவாழ்வும்

மாத்திரைப் போதில் இடு காட்டினிற்

போமென இல் வாழ்க்கைவிட்டு ஏறும்… … அடியவர்போல

In these poems Arunagirinaathar openly and candidly pours out his proclivity to excessive sensual gratifications. He pleads for Muruga-p-peruman’s grace to wean himself away from his weakness, and move him towards the sublime. In his verses, Arunagirinaathar uses first-person singular, indicating his own personal struggle. When we read these poems constructed in first-person singular, we often feel that Arunagirinaathar is describing our own personal struggle on these matters.

A Unique Feature of Arunagirinaathar’s Poems: The schism between the Saiva and Vaishnava schools of worship in the Tamil country through the centuries is well known and there is no need to gloss over this division. Given this atmosphere, Arunagirinaathar is unique in the Tamil Bhakti literature.

Muruga-p-peruman is the son of Siva and Parvathi; with Parvathi being Vishnu’s sister, Murugan is also the nephew of Vishnu and Lakshmi.

Arunagirinaathar uses this puranic fact quite brilliantly and unabashedly in many poems. He would describe Muruga-p-perumaan as the son of Siva; and in the next breath and in the next line, as the nephew of Vishnu. Here is an example:

“O the Crimson-Colored (செய்யோய், a descriptive name for Muruga-p-peruman), the son of the One Who Wears Snakes as Garlands (reference to Shiva), and the nephew of the One Who Sleeps on the Bed of a Snake (reference to Vishnu), please grant me Your Grace.”

There are hundreds of references like this in his poems in which the poet refers to Lakshmi, Parvathi, Rama, Krishna, Arjuna, Ravana, Hanuman, Ganesha, and weaves episodes in the Ramayana and Mahabharata and the puranas into his poems. Why he did this in the 15th century is an interesting question for all of us to ponder over and see its relevance in the 21st century, here in the US.

How Arunagirinaathar’s poems were unearthed is a fascinating story. Arunagirinaathar’s contribution to Tamil literature in general, and Tamil Bhakti literature in particular, will be incomplete without the contributions of these great men:

V. T. Subramania Pillai (1846 – 1909): Till the late part of 19th century, Arunagirinaathar’s poems were not known to most people in Tamil Nadu. They were on palm leaves in homes of people in and around Tiruvannamalai and the Kaveri Delta area.

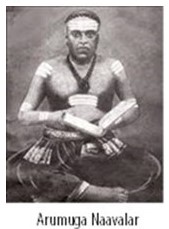

One Shri V. T. Subramania Pillai, a District Munsiiff and Judicial Officer under the British, in 1871 went to resolve a dispute at the Chidambaram Temple; the Temple’s Deekshitars quoted several verses from old Tamil bhakti poetry to make their claims. One such poem the Deekshitars quoted was from a verse of Arunagirinaathar. Fascinated by this verse, Subramania Pillai, a devotee of Muruga-p-peruman, wanted to know more about the person who wrote the poem, and he came to know of Arunagirinaathar. This started Subramania Pillai’s search for Arunagirinaathar’s poetry. He came to know of the sage’s six poems in a book by the great scholar Arumuga Naavalar (1822-1879), who lived in Jaffna, Sri Lanka.

Arumuga Naavalar’s contribution to preserving Saivism among the educated Tamils in Sri Lanka is considerable during the Portuguese and Dutch colonial occupation of Sri Lanka.

Starting with the six poems found in Arumuga Naavalar’s book, Shri Pillai went about his mission in his search for Arunagirinaathar’s works, said to be over 16,000 poems. He ended up collecting from various sources over 3,000 verses on palm leaves. He spent considerable time in sorting out his palm leaf collections, removing duplicates (which confirmed to him the authenticity of Arunagirinaathar’s works) and reconciling the same poems with different similar sounding words here and there. He and his sons Chengalvaraya Pillai and Shanmugam Pillai spent considerable amount of their time and personal resources in bringing out Arunagirinaathar’s poems in three volumes in the late 19th century and early 20th century. The Tamil literary World owes a great deal to V. T. Subramania Pillai and his two sons for bringing out Arunagirinaathar’s works for the outside world.

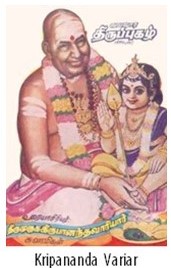

Kripananda Variar Swami (1906-1993): We owe a great deal to Kripananda Variar for painstakingly writing in six volumes detailed commentaries the Tiru-p-pugazh songs, giving word-by-word meaning and explaining the references to all the stories in the songs. This monu-mental work is necessary for anyone wanting to understand the nuanced meanings of the Tiru-p-pugazh verses in the context of Tamil Bhakti literature. Variar Swamy gave countless upanyasams and discourses on Tiru-p-pugazh all over the world. Incidentally, Variar Swamy was the inspiration for the Murugan Temple in Lanham, MD.

A. S Raghavan Sept 4, 1928-May 17, 2013), a government official in New Delhi, was so deeply impressed with Tiru-p-pugazh that he started a bhajan group in New Delhi. This grew over the years with people who learned from him the songs starting local chapters of Tiru-p-pugazh bhajans wherever they settled, including in the US. His group called Tiru-p-pugazh Anbargal (Friends of Tiruppugazh) set up branches in many parts of India and even outside. Details here: https://www.lokvani.com/lokvani/article.php?article_id=9938

For people with a decent grasp of the Tamil language and the basic tenets of the Sanatana Dharma, a very good source for Tiru-p-Pugazh songs and their general meanings is the website developed by Shri Gopala Sundaram at www.kaumaram.com/thiru/nnt0663_u.html. Gopala Sundaram’s website catalogs Arunagirinaathar’s Tiru-p-pugazh songs alphabetically, and also in terms of the temples on which the poems were composed.

You can listen, enjoy, and admire Arunagirinaathar’s complex rhythm patterns in Shri Pondicherry Sambandam Gurukkal’s excellent recordings of Tiru-p-pugazh songs here:

www.tinyurl.com/Sambandam-Gurukkal-1

www.tinyurl.com/Sambandam-Gurukkal-2

Shri Sambandam Gurukkal brings out the life in Arunagirinaathar’s verses with his grasp of Tamil Bhakti literary tradition and musical training.

Arunagirinaathar’s complex meters, Sanskrit and Tamil phrases, and descriptive names for deities in his poems are impossible to poetically translate into English or other European languages; and perhaps even into South Indian languages.

Fred Clothey, who was born to missionary parents in the Tamil country in the early 20th century, is the Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. He spent over 15 years in India, and also worked in Malaysia and Singapore. Clothey introduced Arunagirinaathar to English-speaking readers in his scholarly book Quiescence and Passion (now out of print), focusing on Kandar-Anubhuti and Kandar-Alankaaram. On the difficulty of translating Arunagirinaathar Clothey says:

“[My work] is a classic example of the kind of project into which fools rush where angels fear to tread. Neither my English nor Tamil qualifies me to translate poetically a Tamil poet who remains defiantly untranslatable… … [I got introduced to Arunagiri] in 1965 and sampled the poet’s unusual style. I have since come to know even better why none have dared to attempt a translation [of Arunagirinaathar] save in the most prosaic of ways.”

Tamil scholars in the 19th and 20th century who brought this great poet’ work to public attention are: The Tamil poet Pamban Swamigal (1848 -1929); The scholar-writer Vannasarapam Dhandapani Swamigal (1839 – 1898); A.S.Subramanian known as Thiru-p-pugazh Tha-tha; and Ki. Vaa. Jagannathan (1906-1988).

Arunagirinaathar left his mortal remains when he was 80 years in Tiruvannamalai. Every year in July the Murugan Temple in Viralimalai, (situated 18 miles southwest of Trichy in Tamil Nadu) organizes a music festival honoring Arunagirinaathar.

Arunagirinaathar life story is so captivating that the Tamil film industry made a full-length feature film Arunagirinaathar with the famous playback singer T.M. Soundararajan as the poet Arunagirinaathar. And the Government of India released a postage stamp (INR 50 denomination) in Arunagirinaathar’s honor. Arunagirinaathar’s other works:

• கந்தர் அனுபூதி Kanthar Anubhuthi – 51 verses, each four lines, with four phrases/line.

• கந்தர் அலங்காரம் Kanthar Alangaaram – 107 verses each four lines, with five phrases line

• கந்தர் அந்தாதி Kandar Anthaathi – 100 verses, each four lines, with five phrases/line.

• திருவகுப்பு Thiru Vaguppu

• வேல்விருத்தம் Vel Virutham – 10 verses each four lines, with twelve phrases/line.

• மயில் விருத்தம் Mayil Virutham – 11 verses each four lines with twelve phrases/line.

• சேவல் விருத்தம், Seval Viruttam and –11 verses each four lines with twelve phrases/line.

Arunagirinaathar’s expansive, enigmatic, and in-scrutable idea of Godhead, we can see in the last verse in Kandhar Anubhuthi:

உருவாய் அருவாய், உளதாய் இலதாய்

மருவாய் மலராய், மணியாய் ஒளியாய்க்

கருவாய் உயிராய்க், கதியாய் விதியாய்க்

குருவாய் வருவாய், அருள்வாய் குகனே.

Fred Clothey translated the above terse verse into English, capturing the great poet’s cryptic style in his English translation as well:

Formed, Formless; Being, Non-Being;

Flower, Fragrance; Jewel, Radiation;

Embryo, Life; Goal, Way;

Come Guha, [as my] Guru

[and] Grant [me] your Grace.

Arunagirinaathar’s devotees organize festivals for him periodically at the Tiruvannamalai temple and Murugan temples in India, and in Hindu Temples in Mauritius, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Australia, and North America.

After this discursive discussion, it may be appropriate to end this write-up by quoting a great terse phrase in Arunagirinaathar’s Kandar-Anubhuti, in which the poet recalls the advice Muruga-p-peruman gave him:

சும்மா இரு, சொல் அற,

literally meaning “Be Still, and Speak Not,” or better still, “Keep Quiet and Chatter not.”

It is worth noting that both Thaayumaanava Swamy (1705-1744) and Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950) adopted these phrases in their philosophical/spiritual works. And that is a delightful way to end this write up on the One-of-a-Kind Great Tamil Bhakti poet, Arunagirinaathar.

References:

1. Clothey, Fred, Quiescence and Passion, Publishers: Austin & Winfield, San Francisco, 1996, 177 pp. (now out of print, but available in a few bookstores and on-line book outlets.)

2. www.eng.arunagirinatharmanimandapam.org/scholars-of-tirupugazh/

3. Kripananda Variar, Tiru-p-pugazh Virivurai, in six volumes, Publishers: Vaanathi Pathippagar, T.Nagar, Chennai, 1985 onwards.

4. www.kaumaram.com/thiru/nnt0663_u.html.

5. www.tinyurl.com/Sambandam-Gurukkal-1

6. www.tinyurl.com/Sambandam-Gurukkal-2

__________________________________________

About the author: Kollengode S. Venkataraman, lives in the Pittsburgh metro area since mid1980s, and is the editor and publisher of a 28-year-old independent quarterly magazine, The Pittsburgh Patrika, (www.pittsburghpatrika.com).