From Olympics to college and school sports, we see the natural instincts of youth to compete with each other and display their prowess to an admiring audience. It is an absolute delight to see six- and seven-year-olds running on soccer fields screaming and chasing after each other to snatch the ball and move it towards their opponents’ goal post. This instinct to display physical skills is not only in competitive sports, but also in simple family gatherings, as I found out recently.

We were in California in August for a family wedding, when our daughters also added a few vacation days for us and our grandkids to stay in a rented place. The place had an indoor pool with an 8′ deep diving end. Our nine-year-old grandson, barely 4′ tall, knows swimming and was trying to learn diving from his dad. After a few trials and some serious struggle, he did get the hang of how to dive deep into the pool.

No sooner had he got the hang of it than he wanted to show his prowess to his grandfather, who, growing up in India in the 1960s, was a stereotypical urban kid, not even SEEING a swimming pool. My grandson told me, “Thatha, toss a coin at the deep end. I will dive and get it for you.†I was nervous, not knowing whether he had the lung capacity to dive deep in the pool, search for the coin, reach the bottom, pick it up and come out. He pestered me. I looked at his father, and he said, “Go ahead.”

With hesitation, I tossed a quarter into the deep end of the pool. The kid dived confidently into the deep end, looking for the coin. Then, picking up the coin, and with a great sense of accomplishment, he soared out of the pool like a dolphin with a beaming smile, showing me the coin in his hand. He asked me to do this again and again.

Seeing my grandson trying to impress me with his aquatic skills, I recalled an old Tamil poem I had read decades ago. This poem is in the 2000-plus year-old Tamil classic Puranaanooru.

Puranaanooru is an anthology in the Tamil literature, written by both men and women poets 1800 to 2200 years before our time. The 398 verses are in classical Tamil with very few Sanskrit words interwoven, indicating that Tamil’s history is parallel to Sanskrit’s.

The Puranaanooru verses describe the valor, pride, pettiness, generosity, and even philandering of kings; admonish them to be loyal to their wives; advise kings not to let bureaucrats harass citizens; describe the grinding poverty of citizens during wars, thus trying to dissuade kings from going to adventurous wars.

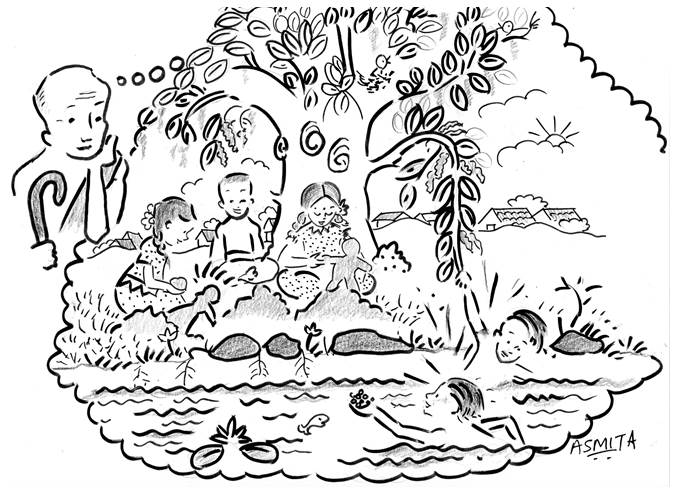

But the poem I recalled is quite different. In this, the poet, Todittalai Vizhuttandinaar, in his very old age, recalls with vivid imagery the innocent days of his youth long gone, very much like my own. He describes the prowess he and his buddies showed in their swimming skills to the admiring onlookers on the banks of a large, deep village pond after the rains. The sentiment the poet expresses is universal transcending time, place, and culture that separate humanity into distinct linguistic, religious, and cultural groups. Here is a free style English translation of the verse:

It feels sad to think about it now.

On the sandy edges of the pond with cool water,

we played with girls who made dolls with the clayey soil,

decorating them with flowers plucked from trees nearby.

Holding hands in the innocence of youth,

we hugged each other, swaying this way and that.

Climbing the Marutha (Arjuna) tree on the bank

with its branches sagging towards the pond,

we dived into the deep pond with a thud and a splash.

Reaching the bottom, we returned showing to the

amazed onlookers on the shore the fistful of sand

we grabbed from the pond’s floor.

Where did that innocent youth go?

Isn’t it pitiful that having become old now, tremblingly

I walk holding a metal-capped stick while coughing,

barely uttering a few words in between?

Sitting on the poolside in balmy California, I was amused to see similarities between my nine-year-old grandson trying to impress me with his aquatic skills and what Todittalai Vizhuttandinaar, the senile Tamil poet, recalled in a 2000-year-old poem on his youth long gone. The Tamil poem in Puranaanooru in its original is available here: www.tinyurl.com/Puranaanooru-Swimming — END