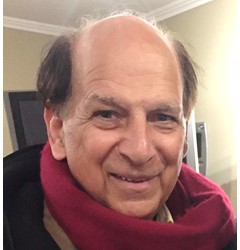

By Juginder Luthra, Weirton, WV

Each one of us gulped down the butter covered fresh rotis with steaming sabzi (cooked vegetable dishes) coming out of the kali covered brass kadaai (wok), lovingly served with mataji’s strong hands and loving eyes. The smile in the eyes matched the one on her full lips.

“Do you have more gobhi?”, even though the rotis were delicious enough alone and the answer was always “yes”. Gobhi is cauliflower in north Indian languages.

We did hear the ladle scraping the walls of the kadaai, which got quickly shielded by a metal cover with a small handle in the middle, which she held with the outstretched end of white sari.

“Eat, there is plenty more,â” she would say. We suspected it to be a lie, but the empty stomachs and young minds were too selfish to worry about her. And she loved our selfishness.

“Toon changa khada mainun aape mil gaya.” I remember her telling us in Punjabi, our mother tongue. “You ate well, it got to me automatically.”

Later, with a satisfied look in those loving eyes surrounded by wrinkles of worries and joy, she took two dry rotis, rubbed them on the katori (a small cup for serving dishes in dinner) which just a few moments ago was overflowing with the home-made white butter she made before the sunrise that morning by churning the home-made dahi (yoghurt).

Placing the rotis on a small steel plate, she crushed a small oval red onion between her two hardened palms, which, years ago, were softer than rose petals. The smaller onions were not pungent, especially the oval central core of the tender ones, unlike the larger ones, which are hard to crush and make your eyes tear. These were not as delicious.

“Somehow onions and humans are not much different,” she occasionally mentioned stoically.

She then pulled out a couple of dripping mango achaar (pickle) slices, also home-made, from the tall pale ceramic jar. Now, with the satisfaction of having nourished her family with food and love, she sat on the cloth woven chauki (a small low-height stool), folded her legs and put the plate on her knees. She scraped the few burkis (roti pieces) along the side of kadai till she could see the shiny walls of the kadai. The rest was enjoyed, relishing it with raw onion and achaar. She ate alone, in peace.

Her husband, our pitaji (dad), also was eating alone in some remote place working in a brick kiln; making barely enough money for his family to survive, helpless victims of the monstrous problems arising out of the 1947 Partition, in which the British in great haste slit India into India and Pakistan, causing misery and mayhem for millions in the Indian subcontinent, thus transforming a prosperous farmer in Pakistani Punjab into a brick maker near Delhi, and a well-to-do family into refugees overnight.

Mataji held the fort at home. With her family safe, well nourished with love and her food, she was content and happy in her kitchen. END